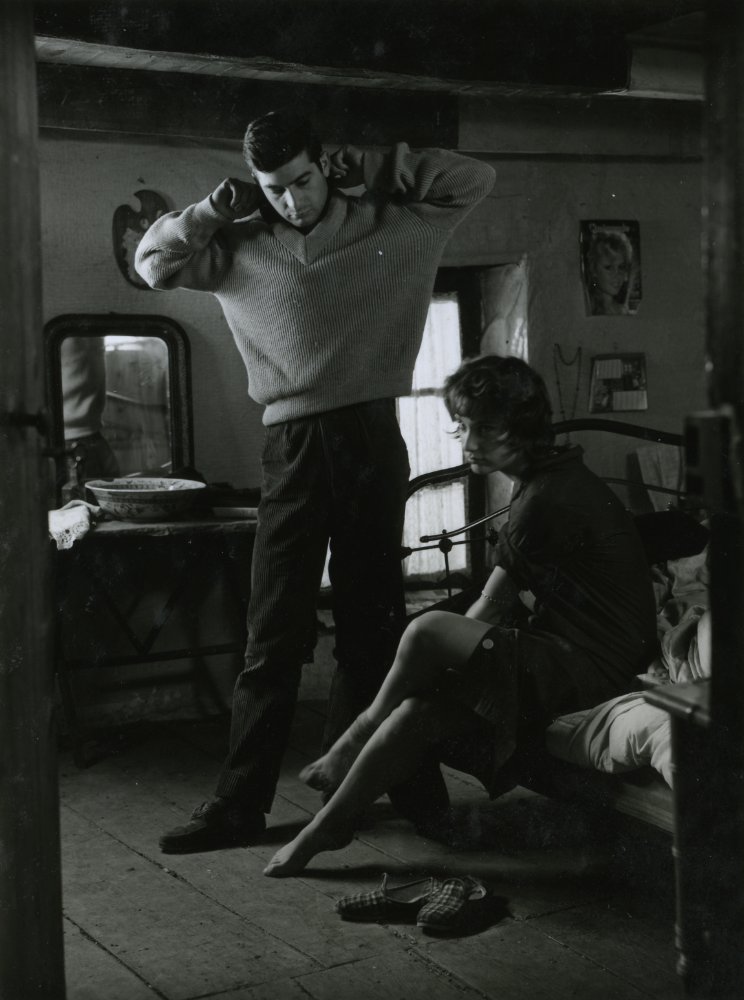

Bernadette Lafont was born at the Protestant Health Home of Nîmes in Gard, the only child of a pharmacist and a housewife from the Cévennes. Her mother always wanted a boy to name Bernard and, once she gave birth to a girl, she enjoyed to hold this against all the catholics she knew as the proof that their God either was blind or didn't exist. Often dressed as a boy and nicknamed Bernard, Bernadette nevertheless had a great relationship with her parents. Having spent part of her childhood in Saint-Geniès-de-Malgoirès, she returned to Nîmes where she took ballet lessons at the local Opera House. She proved to be a gifted student and she did three little tours and about twenty galas there. An extroverted girl with a fervent imagination, she used to spend her holidays at the Cévennes family mansion playing dress-up with her friend Annie, along whom she used to pretend to be an actress from an imaginary West End Club, working in Italian cinema: doing this started to win her a lot of male attention. She also began to develop a passion for film from an early age, adopting Brigitte Bardot and Marina Vlady as role models.On the summer of 1955, the "Arènes" of Nîmes hosted a Festival of Dramatic Arts for the second time: 40 actors came from Paris while 50 regional aspiring thespians and 30 dancing students were recruited on the place. The main attraction was a production of "La Tragédie des Albigeois", a new play which featured music by Georges Delerue and starred, in the leading roles, the acclaimed stage veteran Jean Deschamps and a talented young actor called Jean-Louis Trintignant, who would go a long way from there. The play also offered bit parts to future directing genius Maurice Pialat, Trintignant's then wife Colette Dacheville (the future Stéphane Audran), and the skilled Gérard Blain, who, by then, had already appeared in a handful of movies, although usually in uncredited roles. Having seen Gérard on his way to a rehearsal at the "Arènes", Bernadette was immediately won over by his "bad boy" charm and decided to walk around the place (which had ironically been the spot of her parents' first encounter) to catch his attention: she did. Already separated from wife Estelle Blain, Gérard immediately developed a great interest in Bernadette, stating that he was willing to bring her to Paris to introduce her to certain people at the Opera House and stating how glad he was that she didn't have any interest in pursuing an acting career, something he regarded, in a woman's case, as a road to perdition. After she finished her studies, Bernadette's parents gave her permission to marry Gérard and she did so in 1957.Blain found his first relevant film role in Julien Duvivier's brilliant thriller Voici le temps des assassins... (1956) and Bernadette spent a lot of time with him on the movie's set, something that made her fascination with cinema grow even bigger. The film opened to positive reviews and was also lauded (quite an oddity for a Duvivier feature) by the ruthless "Cahiers du Cinéma" critics, including the young François Truffaut, who called Blain "the French James Dean". Gérard decided to give the critic a phone call to thank him for the kind words and, after the two had a couple lunches together, Truffaut ended up making him a work offer. It's always been very hard for film critics to point at a specific work as the undisputed start of the French New Wave: for many people it's Agnès Varda's La Pointe-Courte (1955) , but the director herself never wanted to be bestowed this honor and prefers to be considered a godmother to the movement. Others think that the roots of this new school of cinema can be found in the early shorts of Jacques Rivette, Jean-Luc Godard and Truffaut. The latter's Les mistons (1957) is certainly one of the most significant of these ground-breaking works and happens to be the project for which Blain was recruited. Truffaut wanted to shoot the short in Nîmes and, with the exception of Gérard, he hired only non-professional actors: this included several local children and, of course, Bernadette. The mini-feature is centered around two lovers, Gérard (Blain) and Bernadette Jouve (Lafont), who are spied on by a group of children and are separated forever once he leaves for a mountain excursion from which he will never return. The character of Bernadette, a head-turner who becomes a great object of attention wherever she goes, was very much based on the real-life Lafont, just like her relationship with her beau Gérard (who has to leave Nîmes for three months, promising to marry her at his return) was very much reminiscent of her engagement to Blain. The two actors stayed at the house of Bernadette's parents for the entire shooting of the short. She chose to act in bare feet the whole time to make a homage to Ava Gardner in The Barefoot Contessa (1954) and, at the same time, a favour to Blain, not exactly a man of exceptional height. When he had married Bernadette, Gérard had sworn to himself that his new wife would have never stolen the spotlight from him like Estella had previously done: unfortunately for his plans, he was soon going to be sorely disappointed. Truffaut managed to get the best out of the young actress through rather unorthodox methods at times (like threatening to slap her hadn't she cried convincingly), but they established a great chemistry in the end and he taught her not to look at someone like Bardot as a source of inspiration, since the big star didn't possess any gift Bernadette should have been jealous of. "Les Mistons" turned out to be a little gem which already contained all the best elements of the great director's cinema. During the shooting, Bernadette got to know many other key figures of the upcoming French New Wave, including Rivette, Paul Gégauff and Claude Chabrol. The latter had already asked her to appear in his debut feature film by the time Truffaut had proposed her to star in "Les Mistons": she had accepted both offers simultaneously and, once the shooting of the short movie was over, she immediately embarked on another adventure.Chabrol's atmospheric Le beau Serge (1958) is now officially considered the movie that kickstarted the French New Wave: it was shot in Sardent, where the director had spent many of his childhood years. The main cast was formed by Bernadette, Gérard and another young actor called Jean-Claude Brialy, who would soon become a cornerstone of French cinema in general and an assiduous presence in New Wave movies in particular. The movie takes place in a community of drunkards and is centered around the relationship between the rebellious Serge (Blain) and his better balanced friend François (Brialy). Bernadette got the juicy role of Serge's slutty sister-in-law and lover, Marie. This role of a very impudent and provocative woman of slightly vulgar charms allowed her to introduce the French audience to a new female image that was very much different from the ones usually found in the cinema of the period and worked as a prototype to the unforgettable gallery of "bad girl" types her cinematic work will forever be strictly associated to. The movie was very much praised along with the great performances of its actors. Bernadette was immediately featured on the cover of a recent edition of "The Cahiers du Cinéma" along with Brialy. Her rise in popularity had predictably an immediate negative impact on her relationship with Blain. The two male stars of "Le Beau Serge" were paired again in Chabrol's subsequent feature, the least interesting Les cousins (1959), but, this time, the leading female role was given to an absolutely unremarkable Juliette Mayniel. Bernadette started to grow more and more bored as Gérard was away from home to shoot the movie and even tried to contact him on the set asking for a divorce.Bernadette teamed up again with Chabrol in the director's third released feature , À double tour (1959), which didn't work as well as a thriller rather than as an ironic spoof on the clichés of the genre and actor piece. The film's acting laurels go undoubtedly to Bernadette as a saucy waitress, Jean-Paul Belmondo as a cheeky young man with an alcohol problem and the glorious Madeleine Robinson (rightly awarded with a Volpi Cup at Venice Film Festival) as a troubled wife and mother. By the end of the year, Bernadette had eventually divorced from Blain and gotten into a relationship with a Hungarian sculptor she had known on her 20th birthday, Diourka Medveczky. 1960 was a turning point for her, as the work she did helped cementing her status as the female face of the New Wave. L'eau à la bouche (1960) was the first and most famous feature of Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, another critic of the Cahiers who wanted to follow the same path of his colleagues turned directors and decided to call Bernadette after seeing "Le Beau Serge". The superb Les bonnes femmes (1960) was Chabrol's fourth movie and remains one of his masterworks. The film follows four girls (Bernadette, Stéphane Audran, Clotilde Joano and Lucile Saint-Simon) who are bored with their lives and waiting for a positive change to arrive, whether it's the coming of true love or the fulfillment of a dream. With many scenes set in the shop where the four characters work (a surreal place where time seems to have stopped), Chabrol was able to create something that seemed to come out of Sartre, managing to perfectly spread to the viewer the sense of loneliness and boredom weighing down the girls, seemingly trapped in the antechamber of hell. One of the film's strongest assets were three performances: tragic actress Joano gave a delicate and poetic portrayal of the ill-fated Jacqueline, Italian veteran Ave Ninchi added a lot of authority to her Madame Louise and, of course, Bernadette did the usual splendid job lending her energetic screen persona to Jane, the obvious haywire of the group, but, at the same time, a character more vulnerable and less gutsy than her usual creations. The movie allowed the actress to stretch her range and gave her a lot of good memories, such as pushing journalists on a swimming pool (which is at the heart of a key scene) along with Stéphane, somehow managing to galvanize the normally extremely shy girl. To appear in the movie, Bernadette had to decline the role of prostitute Clarisse (eventually played by Michèle Mercier) in Truffaut's masterpiece Tirez sur le pianiste (1960), but it was a worthy sacrifice. The same year she gave birth to her first daughter with her now husband Diourka, the future actress Élisabeth Lafont, in the same health house where she was born. Bernadette's next collaboration with Chabrol was the remarkable Les godelureaux (1961), where she got her most memorable role so far as Ambroisine, a girl who gets recruited by Jean-Claude Brialy's Ronald to create trouble in an old-fashioned environment with her modern, liberated persona, but eventually becomes impossible for him to control because of her mean-spirited nature. Her anarchic side was used to full potential for the first time, something that lead to one of the best portrayals of dark lady in a New Wave movie. But, like the other characters in the film weren't ready for a new type of woman such as Ambroisine, the movie-goers of the period seemed unwilling to fall for the charms of this revolutionary type of woman Bernadette was bringing to the screen and "Les godelureaux" was a box office flop, just like "Les Bonnes Femmes" had been. The latter, now regarded as one of Chabrol's best, was also a critical disaster, although Bernadette got positive reviews for her performance. Watched today, it's clear that both movies outclass several entries from the director's most celebrated noir cycle from the late 60's to the early 70's. But considering the tepid impact that her movies used to have with the big public, Bernadette was seen just as a half-star and icon of niche cinema exclusively and her agent used to have much trouble in finding her roles at the time. Producer Carlo Ponti once offered her to come to Italy to do some movies: now that his wife Sophia Loren was moving to Hollywood (not exactly to electrifying results), he thought there was a void in Italian cinema that needed to be filled by a feisty, curvaceous actress. This proposal lead to nothing. A project with Godard never saw the light of the day. Rivette never bothered to answer a letter by Bernadette where she had asked him to cast her in his debut feature film, Paris nous appartient (1961). She was offered her ticket to major stardom with Jacques Demy's Lola (1961), but she had to decline the title role in the movie because she was pregnant with her second child, David. The part eventually went to the limited Anouk Aimée, who gave the best acting she could ever be capable of, but it goes without saying that, had Bernadette played the part, she would have elevated the movie to entirely new levels.The 60s, for most of the time, didn't prove to be a very happy decade for Bernadette as she got to face both a personal and professional crisis. Immediately after "Les Godelureaux", her talents were wasted in several obscure movies and shorts. In 1962 she appeared in Et Satan conduit le bal (1962), which boosted a high-profile cast, but was scripted by Roger Vadim, something that predictably sealed the movie's fate. Although officially directed by one-shot filmmaker Grisha Dabat, the film contained all the worst elements of Vadim's cinema and Bernadette was given such a thankless role that not even she could elevate it. One year later she was without an agent and took a break from acting, also to give birth to her third daughter, the future actress Pauline Lafont. The passion between her and Diourka had cooled down by now and the main reason they stayed together for a few years more was their common love for cinema: he was indeed planning to make his directorial debut. For the time being, they tried to make it work by opting for an open marriage where both enjoyed plenty of extra-conjugal affairs. Bernadette's friends Truffaut and Chabrol couldn't really come to her rescue either. The first sent her a letter which read: "You chose life. I chose cinema. I don' think our paths will ever cross again". The second was now engaged to Audran and was soon to enter a second phase of his career, one where he regularly did films whose central female characters weren't witty, animated provincial girls, but frozen, humourless bourgeoisie ladies that were tailor-made for Stéphane. In 1964, Bernadette had a rather unhappy "rentrée" with La chasse à l'homme (1964) , a very disappointing comedy made by the talented Édouard Molinaro on an utterly unfunny script by Michel Audiard. Her role as a prostitute was hardly one minute long, but she had little money and a ton of debts at the time, so she had to accept everything she was offered. During the decade, she found work in a few more resonant projects such as Louis Malle's Le voleur (1967), Costa-Gavras's Compartiment tueurs (1965) and Jean Aurel's Lamiel (1967), but she was given very indifferent roles in all of them. Once again, going after unusual projects by new, alternative auteurs was the decisive factor that helped her putting her career back on track. In Diourka's remarkable first work, the short Marie et le curé (1967), she shined as a provocative young woman who seduces a priest to nefarious consequences for both. Shortly after, she appeared in the silent movie Le révélateur (1968), which was directed by her love interest of the time, Philippe Garrel, and co-starred Laurent Terzieff, opposite whom she had always dearly desired to act. The film was shot in Spain and Bernadette helped funding it thanks to a loan from Chabrol. At around the same time, she also shot the "conjoined" shorts Prologue (1970) and Piège (1970), which were written and directed by Jacques Baratier and co-starred the great Bulle Ogier. Having seen Bulle in her most acclaimed film role in Rivette's titanic achievement L'amour fou (1969), Bernadette had been astonished by the actress' monstrous amount of talent and was a bit scared by the thought of having to cross blades with her. As two thieves locked in a mysterious house by a vampiresque entity, the two actresses went on to gave a great lesson in metaphysical acting. Closer to an example of visual arts or Noh theatre than a cinematic work, Barratier's double short may feel too extreme even to some New Wave purists, but is nevertheless a fascinating watch and a must-see for the fans of the two ladies, equally impressive in the acting department and perfectly suited to create the needed physical contrast, with the taller brunette adding an earthy element and the petite blonde providing an ethereal quality. Bernadette and Bulle developed a beautiful friendship which lead to several other collaborations. In 1969, Diourka made his first feature film, Paul (1969). Jean-Pierre Léaud, a cult actor if there ever was one, had loved the Hungarian sculptor's previous shorts and sent him a letter asking to work with him, so that he would add another unique title to his genial filmography. He so earned the honour to play title character in Diourka's (only) film, as a little bourgeois who escapes from his family, joins a group of sages and meets temptation in Bernadette's form. None of these works really gave the actress a major popularity boost, however. Unlike fellow female standouts of the New Wave such as Ogier, Edith Scob, Delphine Seyrig, Jeanne Moreau and Emmanuelle Riva, Bernadette didn't have theatrical roots, but this didn't prevent her from appearing in stage productions of Turgenev's "A Month in the Country" and Picasso's surrealist play "Le désir attrapé par la queue" in this period. The official start of her career renaissance came, however, at the end of the decade with Nelly Kaplan's La fiancée du pirate (1969), a retelling of sorts of Michelet's "La Sorcière". Conceived as a monument to her talents, the transgressive movie stars Bernadette as Marie, a village girl who becomes a prostitute to settle a score with society (winning male and female hearts alike) and eventually gets revenge on all her men clients. The vendetta bit had been inspired by an off-screen feud between director Kaplan (an angry feminist) and actor Michael Constantin, who had refused to recite the line 'they were very happy and didn't have children" because he was a family man and opted for a more prudish "they were very happy and had children" instead. Bernadette's fearless performance had such a huge impact that, after the film's release, she got offers to star in porn features along with obscene proposals from the more misguided moviegoers. Once again, the public had proved not to have understood what kind of woman she represented, but auteur cinema was now going to welcome her back to a fuller extent.The 70's were definitely a more successful decade for Bernadette. She was still seen as an alternative actress and was hardly ever offered traditional roles in conventional movies, but she didn't care about it, since she felt more at home in unique experiments such as La ville-bidon (1971), Valparaiso, Valparaiso (1971) or Sex-Power (1970). Moshé Mizrahi's feminist dramedy Les stances à Sophie (1971) offered her one of her best parts as the rebellious wife of an excellent Michel Duchaussoy in one of his least charming roles. Jean Renoir himself was knocked out by her performance. In 1971, Bernadette finally got to work with Rivette for the first time in the director's epic Out 1, noli me tangere (1971), originally conceived as an 8 part mini-series to sell to French TV. The movie is centered around 12 main characters that work as pieces of an intricate puzzle and Bernadette was teamed up with several acting heavyweights such as Michael Lonsdale, Françoise Fabian, Juliet Berto and her former co-stars Léaud and Ogier. She played the role of Lonsdale's ex-girlfriend, a writer he tries to recruit for his mysterious dancing group. The actress, unlike other cast members, wasn't used to Rivette's working method, which involved little explanations and a lot of room for improvisation. Since it took her a lot of time to adapt to this style, she was reproached by the director, who harshly accused her of having chosen not to do anything, therefore hurting her feelings. Eventually these words helped Bernadette to find a way to incorporate her "handicap" into the character, imagining that Marie was experimenting writer's block like she had found herself unable to act. A scene where she and Léaud kept just staring at each other because they didn't know what to say was kept by Rivette because he liked the authentic feeling about it. Eventually French TV never bought "Out 1". Rivette also cut it down to 4 hours in the form of Out 1: Spectre (1972), but both versions were hardly released outside of festival circuits. One year later, Bernadette got to play her best remembered and most iconic role: Camille Bliss in Truffaut's underrated black comedy Une belle fille comme moi (1972). As a girl who's released from prison so that she can be analyzed by a student of criminology, the actress got to play a role that exemplified her career (being 'one of a kind') and felt like the summation and sublimation of all the naughty ladies she had played before: of coarse manners and vulgar laughter, indomitable, unstoppable, irreverent, incandescent and more of a destructive force that she had ever been in any of her previous movies, including "Marie et le Curé" , "La fiancée du pirate" and "Les godelureaux". Her performance won her the "Triomphe du Cinéma Français" and was stellarly received in the US, with "Newsweek" and the "New York Magazine" giving it such phenomenal praise that a French journalist wrote this comment: "Bernadette Lafont, historical monument to the U.S.A.". After bringing the female type she so often personified to its definitive cinematic form, Bernadette gradually started her image makeover. The first example was in Jean Eustache's supreme masterpiece La maman et la putain (1973), where she would have been the logical choice to play the title "whore" Veronika, but was actually given the touching role of the title "mother" Marie. Eustache, another former critic of the Cahiers had known her for about ten years and given her the script in 1971. After reading a couple pages she had been immediately won over and realized how much she desired to do it. The director's towering 4 hour achievement is centered around a love triangle formed of Eustache's screen alter-ego Alexandre (Léaud in his very best performance), slutty nurse Veronika (non-professional actress Françoise Lebrun, whose angelic appearance provided the perfect contrast with the nature of the character) and Bernadette's Marie, Alexandre's patient girlfriend who enjoys a very open relationship with him. Managing to convey an entire era in the characters' long, sublime dialogues, Eustache easily made one of the greatest and most significant movies of the French New Wave. Bernadette's portrayal of Marie showed a vibrant, affecting sensitivity that she had hardly done before, giving further demonstration of her talent and versatility. The film was shown in competition at the 1973 Cannes film festival, where it predictably got a mixed reception: some, including Jury President Ingrid Bergman, hated it, while others worshiped it as the future of cinema. In the end, Eustache was given the Grand Prize of the Jury. The same year, Bernadette also appeared in Nadine Trintignant's Défense de savoir (1973), which was no great shakes, but also starred two of the nation's top actors, Jean-Louis Trintignant and Michel Bouquet, both of which she greatly admired. She teamed up with the two again, respectively in L'ordinateur des pompes funèbres (1976) and Vincent mit l'âne dans un pré (et s'en vint dans l'autre) (1975). She was particularly entertaining in the second as an eccentric rich lady, proving that she could be also very convincing at playing very chic and sophisticated characters. The movie ends on a high note with the actress giving an unforgettable, sexy laugh. Daughters Élisabeth and Pauline were also given roles in the movie. The final great role Bernadette played in this period was in Rivette's misunderstood masterpiece Noroît (1976): Giulia, daughter of the Sun. Centred, like many of the director's works, on the dichotomy between light and shadow and day and night, the movie sees Geraldine Chaplin's Morag ending up on a mysterious island ruled by an Amazon-like society where males are either enslaved or, like in her brother's case, murdered. A great revenge tale not without its 'steampunk' element, the film is certainly highlighted by the transforming performance of Bernadette as a ruthless, modern day Pirate queen, cutting one of her female minions' throat with one of the most frighteningly icy expressions ever recorded by a camera and eventually facing Chaplin in a climatic knife duel on the ramparts. Unfortunately, Rivette's previous feature Duelle (une quarantaine) (1976) had been so unsuccessful that "Noroît " wasn't even released and, to this day, it remains the director's least popular work, which means that many people aren't familiar with Bernadette's sinister, against type performance, which ranks with her very best and is undoubtedly one of the great villainous turns in New Wave cinema. By 1978 there had been another change of muse in Chabrol's movies, as an astounding 24 years old Isabelle Huppert headlined the cast of one of his best works, Violette Nozière (1978), the first of a series of successful collaborations which included the director's number one masterpiece, La cérémonie (1995). Bernadette was given a brief, but memorable cameo as Violette's cellmate. This 1969-1978 period easily represents the zenith of her career. After that, it was a bit difficult for her to deal with the changing times.By the end of the 70's, most of the New Wave auteurs had moved on to more conventional projects and French cinema was entering a far less creative phase. Bernadette's desire to constantly challenge herself and look for different, ground-breaking projects often lead her to be part of totally unremarkable movies. Her nadir was probably represented by her two collaborations with Michel Caputo, arguably the worst French director to ever work with name actors (before he exclusively moved on to do porn under several aliases): Qu'il est joli garçon l'assassin de papa (1979) and Si ma gueule vous plaît... (1981), two supposed comic works that would make Michel Audiard's comedies look like Bringing Up Baby (1938) in comparison. But, although the modern viewer can hardly believe the existence of such detrimental works, they actually weren't unusual products of their time, but clear evidence of a scary change of taste on the public's part. Actresses like Bernadette, who used to mainly work for an audience of intellectuals, had to struggle hard to keep afloat after this change of tide and, in the early 80's, she had to lend her talents to a dozen of movies that weren't worth it. The Lee Marvin vehicle Canicule (1984) was the second occasion she found herself working with a mega-star in an international production since her cameo opposite the legendary Kirk Douglas in Dick Clement's Swinging London abomination Catch Me a Spy (1971). Although she was given a bit more to do this time around, this title didn't add anything to her filmography either. Luckily, this wasn't the case of Claude Miller's L'effrontée (1985) a.k.a. "Impudent Girl". It's very ironic -and certainly not coincidental - that a movie going by this title and starring a 14 years old Charlotte Gainsbourg as a gutsy rebel would also feature Bernadette, who had, by all means, every maternity right on this type of character which had grown more and more diffused on the French screen thanks to her work. But the film had a much different flavour from the actress' vehicles from the 60's-70's: Gainsbourg's stubborn but ultimately good-hearted Charlotte is actually nothing like "Les Godelureaux"'s Ambroisine or "Une belle fille comme moi"'s Camille Bliss and Bernadette's Léone, the new love interest of Charlotte's father and mother of an asthmatic girl, is a very likable and moving character. Having moved on to more accessible projects, Bernadette naturally started to receive more award consideration as well, and her sweet, beautiful performance in Miller's movie was honored with a Best Supporting Actress César, one of the best and most inspired choices ever in the category. Her next project was Inspecteur Lavardin (1986), the second and best movie centered around Jean Poiret's unconventional police inspector and her first collaboration with Chabrol since "Violette". Wearing the most recurring name of the director's heroines, Hélène, she also dyed her hair blond for the first time on his wishes, so that she would have taken a step further in changing her screen persona. She liked the idea and would keep blond hair for the rest of her life. She worked with Chabrol for a seventh (and last) time only one year later in one of the director's most gothic-like works, the underrated Masques (1987), which stars the great Philippe Noiret as a villainous TV presenter worthy of the pen of Ann Radcliffe, Christian Legagneur, who keeps an innocent Anne Brochet imprisoned in his imposing manor and wishes to kill her to get his hands on her fortune. The juicy role of Legagneur's masseuse won Bernadette a second nomination for the Supporting Actress César.In 1988, Bernadette's life was sadly affected by a horrible personal tragedy. In August, she was spending a holiday in the Cévennes family mansion, La Serre du Pomaret, along with son David, daughter Pauline and painter Pierre De Chevilly, her new life mate. On the 11th day of the month, Pauline left the house early in the morning to have a long walk to lose weight. By midday she hadn't come back yet. The family began to worry and David started to look for her. Bernadette was unfortunately committed to appear in a TV show in Nice and she left with her heart in her throat, hoping that, in the mean time, David or Pierre would have found Pauline. That wasn't to be. The family lived many weeks in a state of anguish, using the TV show "Avis de Recherche" to diffuse some photos of Pauline in the hope that someone could have shed some light on the mystery. There were several false reports from people who claimed to have seen her and Bernadette kept fooling herself for a long time, wanting to believe that the quest would have been greeted with success. Tragically, on the 21st November, Pauline's body was found in a ravine. Her death was officially called a hiking accident, although its circumstances are still mysterious to this day and some people considered the suicide theory. Bernadette dealt with her devastating grief by throwing herself into her job: always an extremely prolific actress, she got to work more and more and, as a result, she added a lot of unremarkable titles to her resume. She would still find a few good parts in the following decades.Between 1990 and 2013, the actress added over 70 titles to her film and TV resume. Her talents were rather wasted in Raoul Ruiz's uneven Généalogies d'un crime (1997) and in Pascal Bonitzer's delightfully cynical Rien sur Robert (1999). She shined much more as an alcoholic mother in Personne ne m'aime (1994) (where she teamed up with Ogier and Léaud once more), a former teacher who almost ends up abducting her grandchildren in Les petites vacances (2006), an antique shop dealer who still has a great ascendancy over younger men in Bazar (2009) and a family matriarch in the comedy Prête-moi ta main (2006) opposite Alain Chabat and successor Gainsbourg. Her performance in this movie won her a third nomination for the Best Supporting Actress César. Her massive body of TV work from this period was highlighted by her performances in La très excellente et divertissante histoire de François Rabelais (2010) and La femme du boulanger (2010). She also did more stage work than ever in the 2000s. Starting from 2010, she was again employed for a few projects that had a bigger impact. First she borrowed her wonderful, husky voice to a treacherous nanny in the lovely animated feature Une vie de chat (2010), which was Oscar-nominated. This nasty lady role felt like a homage to the characters that had made her famous. The following year, Bernadette and fellow New Wave legend Emmanuelle Riva were unfortunately the latest victims of Julie Delpy's game of playing director, as they were cast in the actress' catastrophic vanity project Le Skylab (2011). Delpy's latest directorial feature contained all the typical elements that she thinks are enough to make a movie: a seemingly endless family reunion, characters talking about hot hair around a table and a few off-colour gags here and there. The two glorious veterans, sadistically mortified by the granny look they had to sport, did the best they could with the material they were given, but it was just too little to begin with and, consequently, they can't possibly be considered a real redeeming factor of the terribly written, lacklusterly directed and otherwise insipidly acted film. In 2012, Bernadette got her best role in years as the title character in Jérôme Enrico's black comedy Paulette (2012). Enrico's pensioner version of Breaking Bad (2008) sees Bernadette's Paulette, a penniless, xenophobic widow, finding herself in a Walter White type of situation as she gets into drug dealing to make a living and begins to smuggle hashish right under the nose of her son-in-law, a coloured cop. The actress was immediately won over by the script, finding it modern and socially significant and decided to give a strong characterization to her character. Getting inspiration from Charles Chaplin's heroes and Giulietta Masina's performance in La Strada (1954), she provided Paulette with a clown side which came complete with a funny walk and her leading turn proved absolutely irresistible. The film opened to positive reviews and got more visibility outside France than Bernadette's latest vehicles and many were foreseeing another career renaissance for her. Sadly, it wasn't to be.In early July 2013, Bernadette was on her way to her family mansion in Saint-André-de-Valborgne (Gard) when she was the victim of a stroke. Forced to stay in Grau-du-Roi for a while, she had a second one on the 22nd and was quickly moved to the University Hospital centre of Nîmes, where she tragically died three days later. Her funeral took place at the Protestant temple of Saint-André-de-Valborgne on the 29th. Her passing was a cause of great grief for an enormous number of people, as she had gradually become a huge favourite of the French audience and a cornerstone of their cinema, and her colleagues had always adored her on both a professional and personal level. The admiration she had earned through the years had been repeatedly proved by several career tributes, including an Honorary César, the title of Officer of the French Legion of Honour and medals from the "National Order of Merit" and the "Order of Arts and Letters".Bernadette's legacy could never be extinguished, but, in addition to everything she had already bequeathed to cinema, she graced the silver screen for a last time even after her death through her final completed movie, Sylvain Chomet's Attila Marcel (2013). The movie, recently showed at Toronto film festival and released in French theatres, was greeted with positive reviews where big kudos were reserved to Bernadette's portrayal of the eccentric adoptive aunt of Guillaume Gouix's protagonist. With the film's upcoming release in many more countries, plenty of others will have the bitter honour to see her eventually taking leave. Since the 25th October 2013, the Municipal Theatre of Nîmes has been renamed the Bernadette Lafont Theatre to honour the memory of the great actress. A once unforeseeable and absolutely logical reaching point for the barefoot girl biking in the city's streets in "Les Mistons".

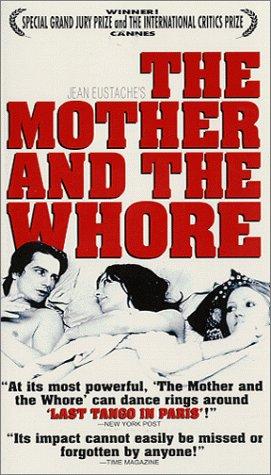

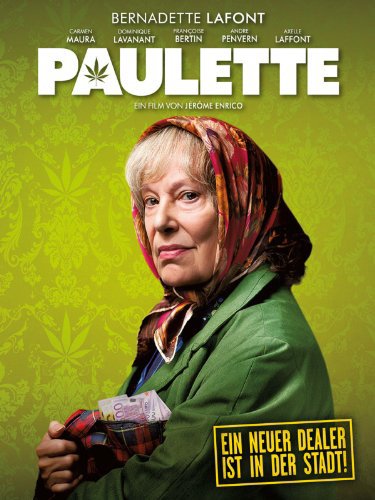

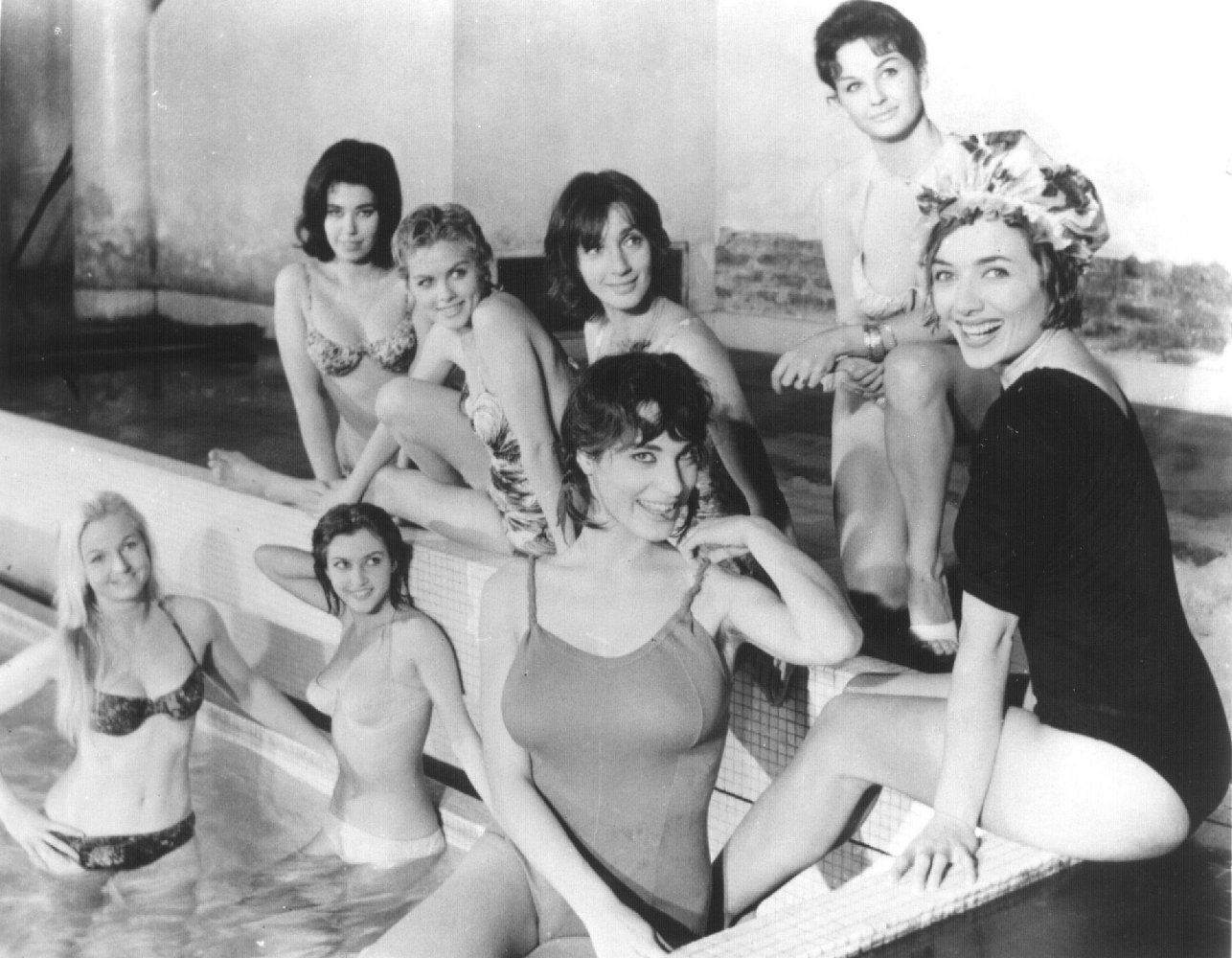

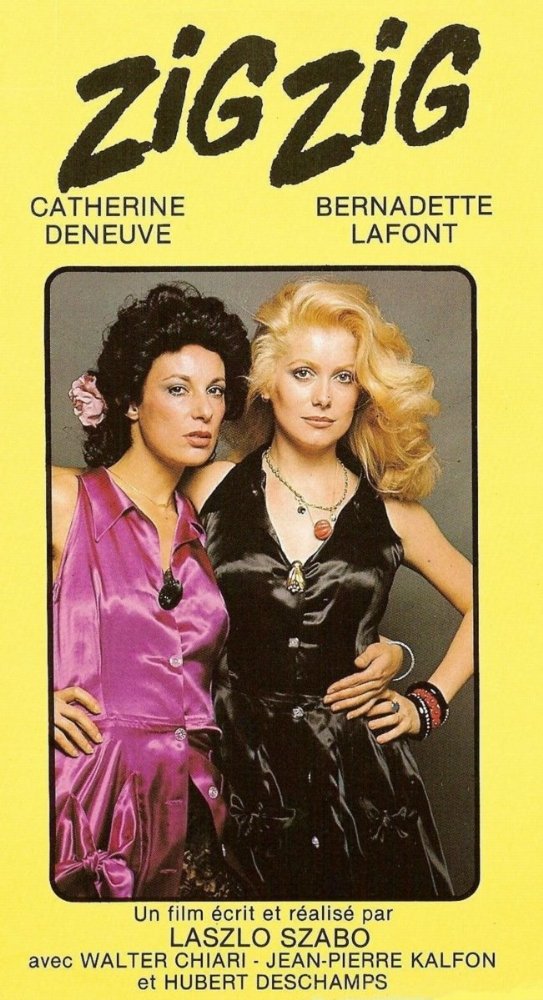

Show less «